There wasn’t any one concrete thing that made me want to read Blood Meridian. I think I knew Cormac McCarthy was a good writer, and I saw the book on the Wikipedia page for “Great American Novel,” so I probably had some vague idea of it being important when I decided to check it out from my university library. It took me 15 days to finish and left me with a lot of thoughts, so I’m writing a review.

Here’s the review: Blood Meridian is really good. If the recommendation is all you care about, you can stop reading (don’t!), but I still have lots more to say about this novel. From what I’ve seen online, nobody has agreed on any one interpretation of the book, so I guess you could call this essay my contention for what I think Blood Meridian is about.

I’m not gonna go out of my way to write spoilers, but I’m also not gonna shy away from them. In any case, the book is 30 years old, so if you get spoiled it’s your own fault. You’ve been warned.

Blood Meridian follows a unnamed protagonist, mostly referred to as the kid. The kid, described as illiterate with an early taste for violence, runs away from home in Tennessee at fourteen, leaving his widowed father behind. Eventually, he finds himself in the town of Nacogdoches, Texas, where he escapes a riot started by a strange hairless man, watches a branded, earless outlaw named Toadvine burn down their hotel, and flees to wander the road again. He’s recruited into an army of nationalist American partisans led by a Captain White; the army is promptly beaten, leading to the kid’s imprisonment in Mexico, where he encounters Toadvine again.

Toadvine negotiates their freedom by signing them up to join a semi-historical pack of mercenaries called the Glanton Gang, which is tasked by a Mexican governor to kill Apache raiders and claim a bounty. The bounty, proportional to the number of Indians they defeat, is paid by the scalp. They go on to fulfill their assignment, but after their task ends, their murderous habits prove hard to break. They continue roaming the desert, adding innocent Mexican villagers, peaceful native tribes, soldiers, and random travelers to their list of targets. Instead of bounties, the men kill for loot, or personal satisfaction, or nothing at all.

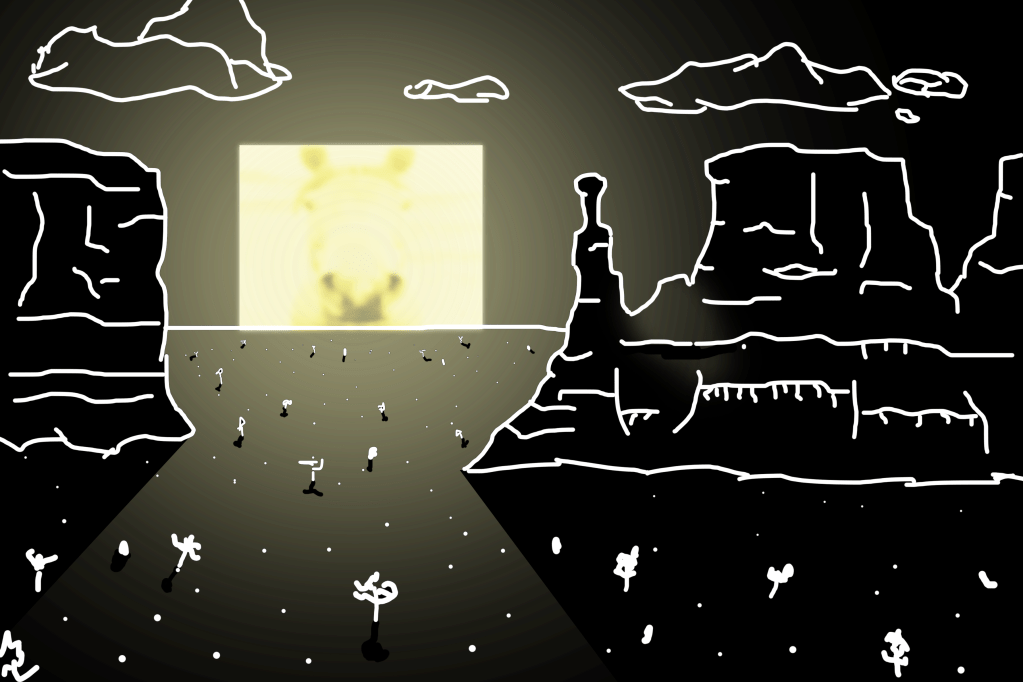

Appropriately, Blood Meridian is known for its uncompromisingly gruesome detail, which is used effectively to describe acts of great violence. In McCarthy’s depiction of the 19th century American Southwest, he paints pictures of mutilated bodies, bespoke firearms, and bloodthirsty armies of raiders set against an indifferent desert landscape. His cast of characters is rendered in verbal portraits highlighting every scar and imperfection, accentuating his characters’ harsh lifestyles. In particular, I appreciated his use of color. With his color palette of blue moonbeams, green pine needles, red sandstone cliffs, tan desert plains, and black blood, the imagery really comes alive.

And the violence itself is what sets the book apart. In McCarthy’s story, violence hangs over every door and lurks behind every corner; characters start fighting with little provocation in conflicts that rapidly escalate. Characters are punched, strangled, stabbed, shot, decapitated, burned, and hung, and the reader frequently watches it happen live, because the protagonists are the ones doing most of it.

Often, the only thing obfuscating the narrative’s horrors from the reader is McCarthy’s style, which is challenging and obtuse. His long, rambling prose ran circles around me, frequently sending me climbing halfway back up the page to retrace the paths of single sentences with jumbled structure and unclear agreements. He used arcane words I’d never seen anywhere else, in English and Spanish and probably other languages I failed to recognize. McCarthy deemed most capitalization and punctuation entirely unnecessary and removed it altogether, including the concept of quotation marks as a whole. I adjusted quickly to the unusual style, but it would give me trouble from time to time, especially when some particularly verbose speakers were onscreen.

Indeed, Blood Meridian often allows its characters to explain themselves at length. These monologues, typically hateful and negative in tone, usually describe a character’s rationale for why they live their life in a hateful way. For instance, Captain White very eloquently explains his specific loathing of Mexicans, a “mongrel race,” to convince the kid to join him in his quest to conquering Sonora for the United States, while the slaver-turned-hermit that hosts the kid in his shack for a night is more generally misanthropic: “You can find meanness in the least of creatures, but when God made man the Devil was at his elbow.”

The kid was an excellent listener, so I heard very little of what he was thinking. In the face of these charismatic speakers, he tends to recede into the background. His small presence leaves a sizeable vacuum which other key characters are happy to step into. Voices like those of John Joel Glanton, the eponymous leader of the Glanton Gang; Ben Tobin the ex-priest, a fellow gang member distinguished by his former vocation; and Judge Holden, the erudite and physically massive antagonist of the novel, often crowd out the kid’s. At times, the reader sees practically nothing of him for chapters at a time, leaving Glanton free to take over the narrative.

It did surprise me to see Glanton become the deuteragonist. Unlike the characters I described two paragraphs ago, Glanton is not much of a talker. Instead, he lets his cruelty speak for itself. He leads the gang on a rampage of killing and pillaging and scalping, with little consideration for the age, gender, or combatant status of his victims.

What’s interesting about Glanton is that the reader can assume his actions to be synonymous with those of the group. When the gang descends upon a sleeping Indian camp and slaughters every last denizen in Chapter Xll, the narrator almost exclusively follows Glanton, with half of the passage describing in detail his routing of six Apache warriors. The kid appears in the scene only once, coming across a fatally wounded comrade:

“McGill came out of the crackling fires and stood staring bleakly at the scene about. He had been skewered through with a lance and he held the stock of it before him… The kid waded out of the water and approached him and the Mexican sat down carefully in the sand. Get away from him, said Glanton. McGill turned to look at Glanton and as he did so Glanton leveled his pistol and shot him through the head.” – Chapter Xll

As the mercenaries become outlaws, their journey through the desert is typically framed by Glanton’s actions. By the time I reached the part where the group is defeated and scattered, the kid was absent from the narrative for so long that I was anxious to see if he survived the final confrontation.

But despite his evil streak, Glanton never occupies an antagonist role. That position goes to Judge Holden. Before I write anything else about the judge, I need to tell you what he looks like: he is a giant pink-skinned gorilla of a man, described as albino, nearly seven feet tall, weighing over 300 pounds, and completely hairless from head to toe, lacking even eyebrows or eyelashes. His enormity requires custom clothes, boots, and hats to be made for him, but conveniently, he often goes entirely naked. Much of his lecturing and wisdom is delivered partially or completely in the nude, which is a frankly terrible mental image, especially since I read him as heavyset so he has the whole quivering-mass thing going on.

One of the concerning things about the judge is that he has chosen to ride around the desert getting sunburned and scalping Indians when he could be doing literally anything else. He flawlessly speaks several languages, is well educated in multiple subjects, and is a skilled rider, dancer, musician, and marksman. As his name might suggest, he is also knowledgeable about the law, and uses it to his advantage when arguing with law enforcement or convincing people not to shoot him. When the gang is camped, we see that he is also an avid naturalist and archaeologist.

“Lastly he set before him the footpiece of a suit of armor hammered out in a shop in Toledo three centuries before, a small steel tapadero frail and shelled with rot. This the judge sketched in profile and in perspective, citing the dimensions in his neat script, making marginal notes. Glanton watched him. When he had done he took up the little footguard and turned it in his hand and studied it again and then he crushed it into a ball of foil and pitched it into the fire.” – Chapter Xl

Later, as the judge sketches a colorful bird he shot, we see that his documentation of the world reflects a deeper desire for power and control. As he explains to Toadvine, the planet will not belong to humans until all of its species are fully known to them.

“I dont see what that has to do with catchin birds.

The freedom of birds is an insult to me. I’d have them all in zoos.” – Chapter XlV

When not lecturing to his illiterate murderer friends or searching the desert for Indians to scalp, the judge pursues his signature set of perverse pleasures. He is implied to be a pedophile and serial child murderer, leaving behind a scattered trail of kids mysteriously disappeared and turned up dead. He is also quite the party animal, shown to love music and dancing and to be quite talented at both. And when a severely mentally disabled man referred to as the idiot begins traveling with the group, the judge takes a special liking to him.

Eventually, the judge explains to the group that he considers his only profession to be war, and everything he does is in service of it. War, in his eyes, is a game, or as my last microeconomics professor might call it, a gamble. The outcome of the gamble is the fairest assessment of who deserves the spoils, and it doesn’t matter how victory is achieved, because there is only one last man standing. Even a game left entirely to chance is a valid determinant of merit, because there is still a winner and a loser.

“Seen so, war is the truest form of divination. It is the testing of one’s will and the will of another within that larger will which because it binds them is therefore forced to select.” – Chapter XVll

War is a key theme of Blood Meridian, and Judge Holden, being the main antagonist of the book, embodies that theme and many others. But while most of the discussion I’ve seen of Blood Meridian centers around its cynical outlook on mankind’s affinity for violence, I believe the novel’s most important theme is destiny.

The judge, with his absolutist might-makes-right mentality, believes that the strong have the right to choose the destiny of the weak, and his behavior reflects this. For instance, his relationship with the idiot is like one between a master and his pet; he enslaves another human because he wields the power to do so. This is also reflected in the judge’s enjoyment of violating children. Because kids are dependent on their parents, they have no real power, so the judge can treat them as he likes. This subtext sheds disturbing light on the nature of his relationship with the kid.

Despite being the novel’s nominal protagonist, the kid spends most of the book following others. He joins Captain White’s crew, then the Glanton Gang, where his actions and motivations can easily be assumed to be one with those of his leader. Like his name suggests, he is little more than a child, and like a child, he has no agency of his own. Having left home, he is without a paternal figure to steer him, and the judge is happy to fill that space.

[Click to skip ending Spoilers!]

After the dissolution of the gang, the kid regroups with Tobin the ex-priest in the desert. Judge Holden, leading the idiot on a leash, pursues and threatens them, taking potshots and lecturing to them on why they should surrender. The ex-priest, shot in the neck, urges the kid, who holds their only gun, to ignore the judge’s words and shoot him: “Dont listen… Do you think he speaks to me?”

Towards the ending of the book, the kid is arrested in San Diego for his involvement with the Glanton Gang. The judge visits him in his cell and says he has testified against the kid to the authorities, and that the kid is to be hanged. The kid listens to him from the shadows in the back of the cell, and the judge invites him to come closer:

“Dont be afraid, he said. I’ll speak softly. It’s not for the world’s ears but for yours only. Let me see you. Dont you know that I’d have loved you like a son?” – Chapter XXll

When the kid refuses to come forward, the judge accuses him of dooming the gang by having moral reservations against its actions, claims that he was preventing Glanton from killing the kid the entire time, reveals that all of the lectures in the desert were for the kid’s benefit alone, and leaves. Days later, the kid is somehow released.

In the book’s final chapter, nearly thirty years have passed since the kid left the Glanton Gang. Now 45 years old, he is referred to as the man. Roaming the wilderness, he encounters a hunter and a pack of orphans, whose stories both involve themes from the judge’s previous lectures- but we don’t have to get into all that right now. The man wanders into a town and sits down at a party in a bar. Incredibly, a bear—a literal bear, like an animal— is dancing alongside the entertainers. A fight breaks out, a pistol is drawn, and the beast is shot and killed. And sitting across from the man is Judge Holden, who appears to not have aged a day since we last saw him.

The judge heads on over to him, greeting him as the only other living veteran of the Glanton Gang. The man says he has to go and reaches for his hat, but he does not move. The judge pours him a whiskey and commands him to drink, and he does. The judge asks: “Was it always your idea… that if you did not speak you would not be recognized?”

The judge proceeds to deliver his final lecture of the book: he claims that every patron in the bar is part of a great choreographed dance, and while none of them can understand how they came to be there, it is not important that they do.

“Let me put it this way, said the judge. If it is so that they themselves have no reason and yet are indeed here must they not be here by reason of some other? And if this is so can you guess who that other might be?

No. Can you?

I know him well.” – Chapter XXlll

He then claims that as society ceases to settle disputes with war, its warriors will be pushed out of the dance. The dance will then lose its meaning, and only one “true dancer” will remain: he who has given himself entirely over to war, he who has experienced its wildest horrors and learned that he enjoys them. Only that man will dance, and all others are doomed to eternal obscurity. The man replies, gesturing at the dead bear: “Even a dumb animal can dance.”

Hours later, the man leaves the party to use the bathroom. He finds the judge sitting naked and smiling on the toilet. The man is pulled inside and the door is latched behind him.

Afterwards, the judge dances naked on the party floor, towering over the crowd. He crows that he will never sleep and will never die. A bathroom-goer opens the closet and exclaims in shock, but whatever he sees in there is left unclear, unusual for a book full of graphic description. Whatever it was, I think we can safely assume that the judge killed the man in the closet and left him there.

[End of spoilers.]

Like I said, people usually remember Blood Meridian for its message on violence. Because Judge Holden is the centerpiece of the narrative, one could interpret his actions as highlighting mankind’s potential for brutality. One could point to the ending and claim “McCarthy is saying here that might makes right, because the kid represented one thing and the judge represented another and they fought and we can obviously see how that turned out.” However, I don’t think that’s what McCarthy was getting at.

To me, Blood Meridian’s key message is that if you don’t choose your path in life, someone else will choose it for you. The kid, with his fading in and out of the narrative, exemplifies this. From the moment he breaks free of his father, he wanders aimlessly working odd jobs until he is convinced to enlist with Captain White. Even the decision to join the Glanton Gang was not his, but Toadvine’s.

Judge Holden is a foil of sorts because he is all about dominating others. For instance, he makes the idiot his pet, and he abuses his power as a giant well-armed mercenary to abuse defenseless children. His dance metaphor is an analogy for fate, with the one true dancer being the one who is completely free, beholden (lol) to no one. As we can see from the ending, he believes himself to be that one true dancer. His dedication to war, the “truest form of divination,” makes him the sole immortal conductor of history, the only man who can decide the fates of others. Judge Holden believes might makes right. But I disagree.

I said that the judge could be doing anything he wanted anywhere in the world, and that is true. He has chosen to be in the desert killing Indians. However, the others that he has made choices for—children and the mentally disabled— are not capable of making those choices themselves. The kid, a teenaged orphan adrift in the world, is another one of his control freak projects, but this project yields only mixed results. The judge, by his own admission, was attempting to influence the kid for the entire story, and he does show some ability to affect the kid’s decisions. But ultimately, the judge is met with frustration: in his final discussion with the kid, he tells him: “I recognized you when I first saw you and yet you were a disappointment to me. Then and now.”

Judge Holden is no great general orchestrating fate; he can only wield his influence against those too weak to withstand it. Tobin, warning the kid about the judge, is living proof of how a grown man with an education can resist the judge’s control.

In my reading of Blood Meridian, you don’t need to be the strongest man in the world to control your own destiny. You just need to know what you want.

That’s about the end of my review. I had a lot to say about this book, so it feels good to get it all out. I should make it clear that while this is my original take on Blood Meridian, I may have been influenced by the book’s Wikipedia page, which I usually read after I finish a good story. I definitely recommend Blood Meridian, but it’s also definitely not for everyone. I read No Country for Old Men, McCarthy’s most famous book, afterwards, and it took me like two days. Maybe test him out with that one before you dive into all this.

Furthermore, I’m sure Cormac McCarthy knew plenty about abuses of power over vulnerable people, because he dated a 16-year-old fan when he was 42. Go figure, I guess. Thank you for reading.

Response

[…] life. I always try to make sense of fiction before I look up the official explanation (like I did here), but when I accept defeat and open up that plot summary, I feel nostalgic for high school English […]

LikeLike