I’m expanding my reach, growing my brand, pushing the frontiers of networking. A couple weeks ago, I gave my website URL to six different Hasidic guys from Brooklyn.

I was in Williamsburg to celebrate Purim, a Jewish festival of survival. I was there specifically because my friend Marshall had brought me and our friends out with him. Marshall had told us stories of the things and people he had seen while attending the festivities in 2023, tales of burning Israeli flags and typically straight-laced Hasidic men stumbling drunk in customary long coats and black hats.

I had taken walks through the Hasidic part of the city before and found it a frankly gloomy place. When every man in the community wears a uniform, a beard, and sidelocks, it’s impossible to not stick out, and people on the street makes sure you’re aware of that when they stare you down like the outsider you are. But on Friday, March 14, the sun was shining, smiling Hasidim asked me for portraits, and moods were buoyed by the Yiddish techno music continually thumping from distant speakers. Naturally, I had come prepared to shoot. I carried a Minolta X370S on loan from my school, two rolls of Kodak Tri-X 400, and a scavenged auto winder.

Purim commemorates a biblical narrative in which a man named Mordecai and his cousin Esther, the queen of the Persian Empire, foil a sinister scheme by wicked viceroy Haman to exterminate the nation’s Jews. By the end of the story, over 75,000 Jew-haters have been killed, and Haman has been impaled on the 75-foot pole that was erected for Mordecai. After the nation’s Jews celebrated their reversal of fortune, Queen Esther declared the annual festival of Purim, which designated two days for eating, drinking, and giving gifts.

As one man explained to us, this is how Jewish holidays tend to work. “They kill us and they win, we fast,” he said. “They kill us and we win, we feast!”

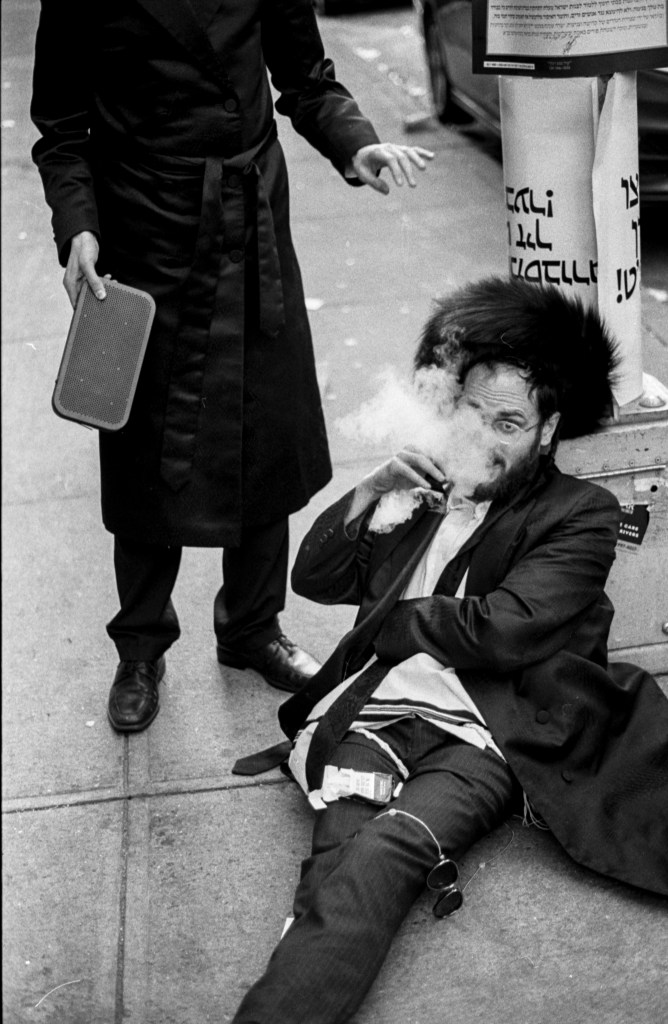

Our new friend had indeed feasted; he proceeded to fold drunkenly over a lamppost and lie on the ground, indifferent to his embarrassed friend trying to return him to his feet.

He was preoccupied by the contents of the coat pockets. In between periods of intense digging, he set a colorful vape, an iPhone, and a handsome pair of sunglasses, with twin lengths of chain strung from its temples, beside him. He offered us a “bump” of the vape, then pulled up the website of his sunglasses business on his phone. The pair he was carrying cost $180, generously marked down to $36. Marshall asked him if the business was profitable. He responded: “I lose money every day.”

Through a cloud of vape smoke, he spotted me with my camera to my face and raised his hands to protect himself. “Hey, $5 for a picture,” he said. “We’re Jews, you understand. We have to monetize our faces.”

Eventually, he found what he was looking for: a checkbook, shielded by a translucent plastic protector. He handed me a leaf and bid us farewell. I looked down on it as I walked away. It read: “The amount of One Dollars and Zero Cents;” “This is not a check.”

I learned that day that there’s a Purim tradition of handing fake money to children, which was why we saw kids running around with big wallets and stray banknotes on the ground. As a Jew myself, I thought it a bit on-the-nose.

People got very excited when I told them I was Jewish. Many of them saw a future for me in their community. One man named Abraham wearing a Asian conical hat nabbed a curl of my hair spilling from under my cap and said “No payes, ah? Maybe one day.” Another man asked me where I was going for the Sabbath, and had I not instinctively said I was heading home, I’m sure he would have invited me into his brownstone. The most memorable response was the short old man who pinched both my cheeks and exclaimed “You lucky! You lucky!” while I made uncomfortable eye contact with the globules of snot poking from his nose. To my astonishment, I glimpsed his uncovered head for a moment (orthodox Jews are supposed to cover their heads at all times) as he snatched my hat off and swapped it with his yarmulke, then pulled his tallis out from under his coat and put it over my neck.

For a surreal moment, I was just one of the guys, dancing arm-in-arm in the street. I was having such a fantastic time that I’m sure I looked completely ridiculous in the video a Hasidic guy was taking of me on his phone. My camera bounced abandoned on my neck without any hands to stabilize it. But in the back of my mind, I thought about how I wanted a picture of the old man, and how I wanted my hat back. The picture unfortunately escaped me because another man who saw the spectacle came up to me and did the same thing again, but I did keep my hat.

The sun was going down by then, and someone cautioned me that I only had a few minutes to finish shooting before Shabbat began. He told me that I still had time to start keeping the Sabbath and doing mitzvot, and if I did, God would love if as I had always done so. He, like all others I had met, seemed surprisingly tolerant of my lackadaisical Reform Judaism. It was more tolerance than I had expected from such a conservative sect, notwithstanding characters like Abraham in the conical hat or the boy in blackface and a dreadlocked wig.

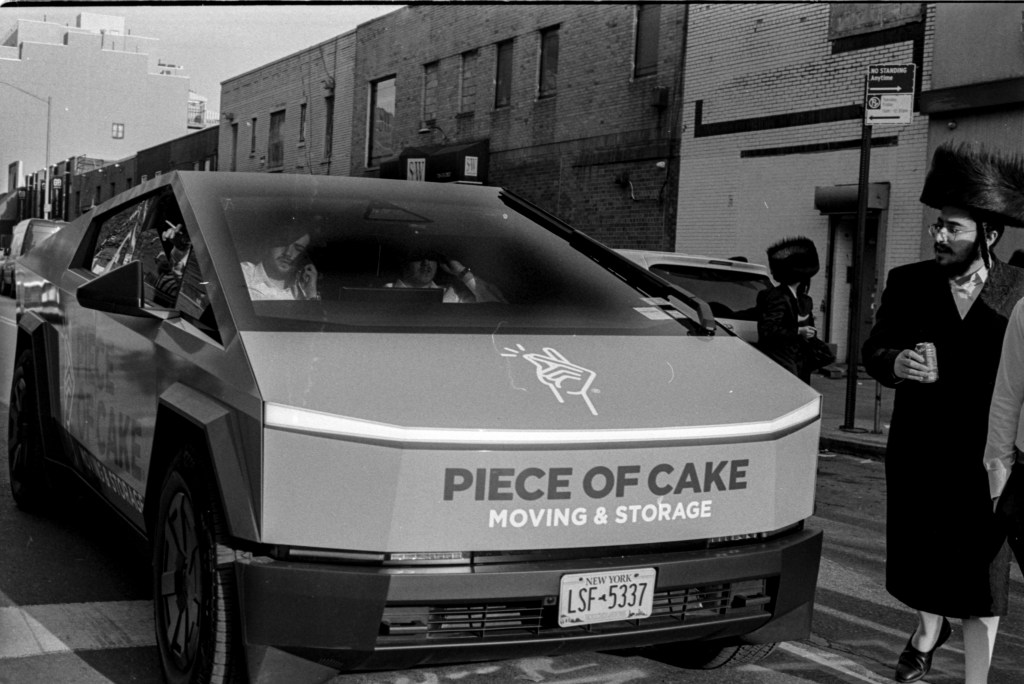

I kicked myself for not photographing the boy, but as I would see, there was no way I could have gotten everything. Towards the end of the evening, I saw another photographer hunched next to a van cheerfully painted with political slogans, trying to frame a shot in its driver side mirror. I waited for him to put down his camera before I asked if he was shooting for anyone (classic networking maneuver — old reliable). We got to chatting and he showed me the annual Israeli flag burning, still smoldering in his LCD display.

The photographer (above, left) told me his name was Billy Dinh, but I already knew who he was. Mostly for his photos of Hasidic Jews.

It’s hard to say which one of us was more of an outsider. I’d celebrated Purim before. The Jews of Williamsburg welcomed me as almost one of their own, but I am ultimately a stranger to their community. We are only vaguely familiar with each others’ lifestyles, and our similarities are nominal. Meanwhile, Billy has been photographing them for years, and I feel he knows just as much about their traditions as I do, if not more.

If I come back to shoot in Jewish Williamsburg, it won’t just be because Purim was the most fun I had doing anything all year. I want to get to know the people who live there. The worst street photography, in my opinion, is characterized by a superficial or nonexistent connection between the photographer and his subjects, so I need to have at least some relationship with the Hasidic Jewish community. Something is better than nothing.

My friends and I got to know Abraham when he accused my friend Rowan of being a liberal because he was from California (it was a good guess). After explaining why he (like the overwhelming majority of Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn) had voted for Donald Trump in 2024, he preached to us about the importance of mutual respect. Our lifestyles being different, he said, didn’t mean we have to force our choices on one another, which meant that we shouldn’t have to be orthodox Jews walking around in coats and hats all the time and that the city government shouldn’t ban plastic bags. When I told him I was Jewish, he threw his arm around my shoulder and started dancing, and I handed my camera to my friend to take a picture of us. But he only managed an unfocused frame of the back of my head, watching as Abraham hoverboarded away.